The beginning of the third week in September has a distinctly different feel to it. Something wonderful this way comes. It is the Tunbridge fair.

Paul and I talk about who will check the fair schedule, feed the dogs, and bring sheep up so that we are ready to leave as quickly as possible. It is only Tuesday.

I send the kids all emails or I leave a singing voice message on their phones alerting them that it is Tunbridge week. Three out of four sons live out of state so this act is an homage to a tradition that pre-dates their existence. They wait for photos and a blow by blow description of fair food eaten. Tradition also dictates that, during the duration of our time at the fairgrounds, we are only allowed to eat food that seriously clogs our arteries. We love Sweets and Beets which are sweet potatoes and beets thinly shaved into chips. The only thing that qualifies them as fair food is the deep fryer – otherwise they are vegetables and I’ll hear about it, with a groan of disappointment, from somebody. I love the soft pretzels which are on the borderline of not-qualifying- if you have one dipped in chocolate, you are OK – but I really like them plain with a dab of yellow mustard and sometimes have to sneak off by myself to grab one so that nobody will confront me about my semi-healthy choice.

Friday night we load the truck with military precision and head out. The fair is one hundred and fifty one years old: there have been only two years when it closed- the Spanish flu and Covid pandemics. The fall without the fair was bleak.

The fairgrounds sit in a beautiful bowl in the middle of Tunbridge (pop. 1337). Josh and I talked about other old fairs and determined that what sets Tunbridge apart is the location. When you are on the fairgrounds you can look in all directions and see mountains, farm fields and beautiful white New England farmhouses. We choose to attend, for the first visit, in the evening because once darkness falls, the fair lights up. I stand by the Ferris wheel, pretzel in hand, and feel the wind blow my hair as I watch fair-goers circle round. I watch the faces of parents and children; mothers using their super powers to hold their child tight against them, the children laughing and pointing, their faces smeared with pink sugar. I see lovers pushed close [to each other] together, too busy looking at each other to notice the fair below. The wheel, lit up, is most wondrous at night. We can’t see the rusted bolts or the paint chipping from the swaying baskets. It stands, majestically, in the center of the fairground, towering above the more modern, music thumping rides.

We sit on wooden bleachers and watch the horse pulling. I make sure Paul has checked the schedule so we can be on time. It begins, he tells me, at seven o’clock, like every other year. We arrive at the pulling building and meet Josh and Al. All of us have hands full of food that we balance as we climb up into the bleachers. We comment on the size of the horse teams and marvel at their gigantic hooves. Farmers sit in front of us in baseball hats and suspenders, leaning back and making running commentary on what the driver is doing incorrectly.

Afterward we stroll toward the agricultural buildings. As we walk we are constantly on the lookout for the next fair food. Will it be the once-a-year sausage, onion and peppers for Paul, or will we be adventurous and try something new…? Perhaps both.

I have wonderful memories of driving home from the fair, four boys in the back dozing. I can see their sticky faces in the light from the oncoming cars. Their eyelids flickering as they dream fair dreams. Clutched in their grubby fists are blow-up swords, a small stuffed animal or a goldfish in a zip lock bag. Once in a while I’d hear a groan as their stomachs worked to digest wads of blue cotton candy. I remember that deep sense of satisfaction that I’d have because my boys were happy in that special way that the fair makes kids happy. When I take the time to figure out why I love the fair so much, I think that I like this answer.

Josh, our youngest, is a grown man now, living in his own home, but I’d find myself sneaking looks at him in the stands to see if he was that special happy again.

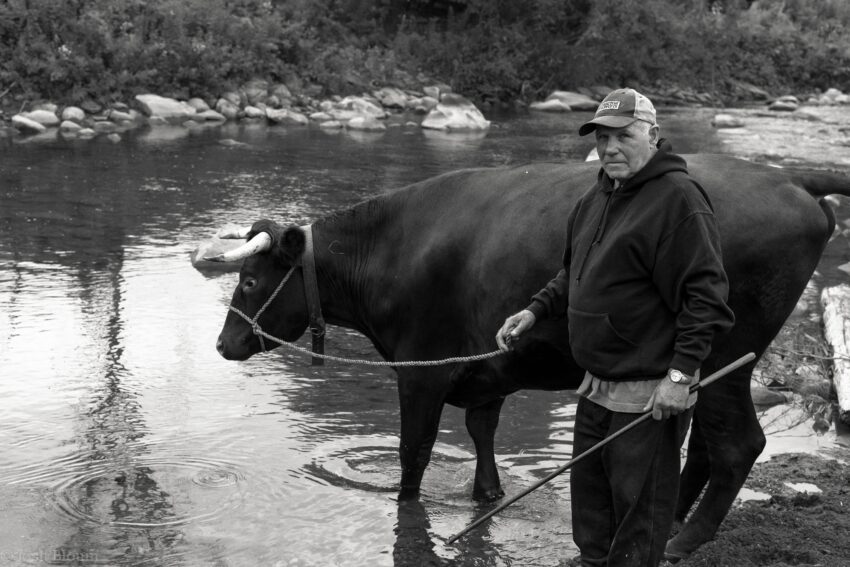

Saturday is day two of the fair for us. We arrive at the fairgrounds, pockets a little lighter, so that we can see all of the things that weren’t open the evening before. Everything looks different in the afternoon sunshine. As we walk across the cow bridge that gets you from the parking lot onto the grounds, there are crowds of people. The fair brings Vermonters out in the same way that it did at the turn of the century. The animal barns are filled with farmers, their kids and cows. They sit on hay bales, hats titled back exposing their suntanned foreheads, their arms crossed talking farming. The faces at the fair are those of hard working, tough and decent people who have taken a moment to let down, relax and enjoy themselves with friends and family. I stand still in the middle of the crowds for a moment and feel ancestral memory wash over me. I know my grandparents and great grandparents were on these same grounds. I step forward with deliberation, following those footsteps.

We crowd around the largest pumpkin, marvel at the twelve foot sunflowers, lean in to check out the quilts and point at the blue ribbon green beans. Cabot cheese is giving away samples of cheese and chocolate milk and we take a minute to talk with the local bee-keeper association, of which we are a member. We take anything they are giving out; free stickers, wooden postcards, cider samples and cuttings of Christmas trees.

At the top of the hill we sit for a moment in the big white tent that houses the Ed Larkin Contra-dancers. They spin around in their turn-of-the-century outfits as the fiddler saws another jig. We all clap enthusiastically and the men tip their tall black top hats. I want to believe that these dancers will be here forever, but they are all getting older and I see them stumble a little as they swing their partners. I look around the tent and wonder if any young people will be drawn to this, will be willing to put on the dusty outfits, or if I am watching it all fade away.

We know every corner but have to see it every year. We push postcards into our pockets from the printing press, listen to the pop of the steam engines as they grind corn into meal and look at all of the old farming implements all shined up again. From above, the smell of the fair is intoxicating, even with full bellies. The scent of warm apple crisp is almost impossible to resist but we make one last food choice and go with a maple milkshake from the sugar shack at the base of Antique Hill. We tug on the straw and talk about the taste as if it is the first time we have ever had one.

When it becomes time to leave we stall. In the pit of my stomach I feel uneasy and it is more than the maple milkshake. I don’t want to leave this place for fear that I may not return, or that it somehow will change in the long year that is coming. I glance at my tall son, now a bearded man, and can see time passing. We slow our steps and savor these last few minutes.

As we pass the Oxen barns one final time, we duck in, again stalling. We shuffle our feet in the fragrant sawdust and I stop to watch a high-schooler mucking out a stall. He takes his shovel without being asked, and bends over to begin. His look-alike father sits in a chair in the corner talking quietly, their stall decorated with corn stalks and pictures of this same boy growing up on their farm. As he finishes he walks past his oxen team and reaches out to pat them on their huge backsides. Caring for these animals, taking responsibility is something he doesn’t need to be asked to do, it is in his blood now. He can’t realize that doing this is teaching him so many things about what it will mean to care for a farm, for family, for his future. But I do.

We leave the barn and pass back across the cow bridge one final time, this direction away from the lights and the laughter. We pull the truck out of the field and over the covered bridge, each of us quietly taking one final look. In two days the fields and buildings will stand empty again. The big barns, their stalls chewed by years of horses, now filled only with ghosts.

As we drive away, I notice that I feel something in my stomach again and it is not caramel apple.

I am filled up with gratitude.