We grabbed the three dark bags bulging full with wool. Some that hadn’t found its way into our last shipment to be made into blankets and some from a recent shearing. We’d decided to use this smaller batch to make some specialty yarn from a small Vermont mill that we had heard good things about. We pushed it into the back seat of the truck- it immediately filled the space with the wonderful, distinct smell of lanolin – hopped in and headed out. Late September is the perfect time for adventuring in VT. The temps have lowered into the fifties or sixties making it just right for long sleeve flannel.

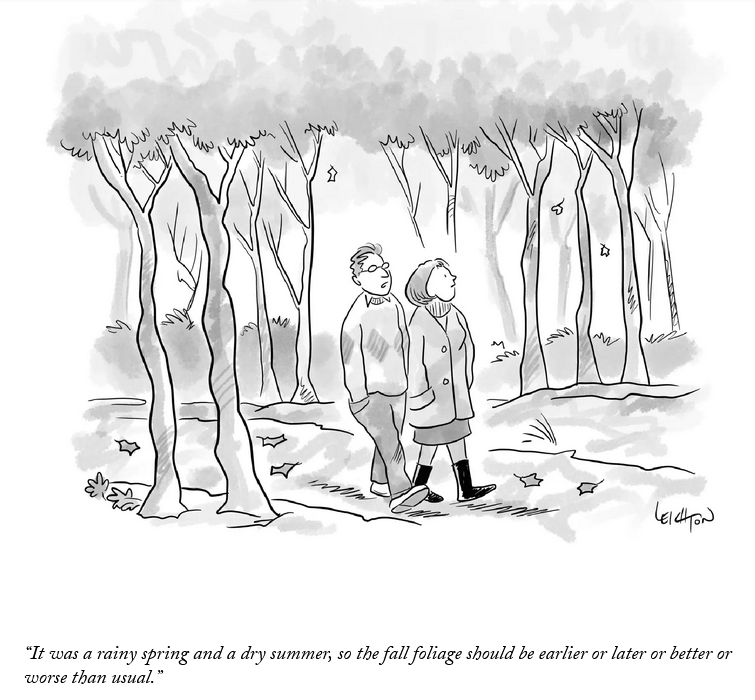

We oohed and ahhed at the foliage which, like the weather, is always hot topic in our area. Even if you live here, you talk about foliage. As we made our way toward the mill, Paul opened by stating that the colors seemed a bit muted. The only way to make this statement is firmly, otherwise there will be an immediate counter, making note of a startling streak of red,. Because I love him, I merely said, “really? I had noticed some brighter colors coming.” This launches the discussion on both what constitutes “muted” colors as well as various theories on why colors are the way they are. We love that one. We might tell you that the reason the colors are muted is because we have had such a dry summer. Next we decide that it is a good frost that is the cause of the brightening of the foliage. We all pretty much go with some kind of water-theory in the end.. Sometimes we can’t remember from year to year which way is which, that means one year we’ll tell you that the colors are bright because it was such a wet summer and the next year we’ll tell you that the colors are pretty darn dim because it was such a wet summer, don’tcha know? Doesn’t really matter because once that conversations ends, there is always the weather.

We dipped into a valley and turned onto dirt roads. The final hill made me glad that we decided to bring the truck as we bounced through the ruts into what our GPS told us was the correct address. There was no sign, but that didn’t surprise or throw us. We drove past the chicken coup filled with colorful hens and a magnificent rooster strutting around to a large garage building with racks of telltale wool drying outside it. A few dogs hobby-horsed to our car, we gauged the barking as half-hearted and so got out. In a few moments Greta came out to greet us. She had a broad, friendly smile and grabbed one of the bags to haul inside. We entered the mill to the noise of a washing machine chugging and said hello to the backside of Greta’s helper as she used a long stick to shove wet wool down into the machine. Piles of wool seemed to be everywhere. Soft puffs of roving and twisted knots of finished yarn in all colors. Strands of wool draped over some kind of machine that Val split her washing machine time with. She moved quickly in her bright orange Crocs, running her hand over the wool to determine something important and then returned to the washer.

Greta began by digging into one of our bags and lifting out piles of fleece. In a very few minutes she had determined that this fleece had too many burdock’s to put through their machines. I realized that somehow we had grabbed one of the discard bags in our hurry to leave the house. I apologized and Greta smiled at me and said, “oh- you’re OK.” Just to be safe we decided to dump the remaining bags of wool out onto a sorting table to be sure we were going to have the prerequisite twenty-five pounds. Greta had to run her daughter to gymnastics so Paul and I pushed up our sleeves and began carding (sorting) the wool. We thought this had been done at home but, embarrassed, we felt that we should do it once again before leaving the mill.

Val worked efficiently. While Greta was dressed in jeans and flannel, Val had on leopard print leggings and a tank top to counter the heat of the work. Her hair was twisted into a braid that dropped across her right shoulder and a small gold nose ring caught the sunlight coming through the window. We all worked quietly until I asked if I could bother her with some questions.

She had learned to knit at her mother’s knee and had rapidly become a hand spinner. After years of that she began to work out clothing patterns for other people to knit. In time she landed a big-deal job designing at an outdoor gear company spending the next twenty years creating. Fatigue set in, as it tends to do after that length of time in one job and she eventually quit. Now she designs periodically and works part time at this mill with Greta. I watched her move with quiet confidence. No piece of paper with a gold seal adorns her wall and yet this woman is, without question, a true expert at what she does and lives a life filled with purpose.

We talked about starting new things and how learning about them is mainly about doing them. I admitted that I am not a knitter and this project with my wool was both an experiment and a learning experience for me. As I sorted wool I confessed that I lacked confidence when participating in wool- group projects. I doubted myself and even the things I believe I know very well: the imposter syndrome surfacing. She rested her hand on her stick and looked at me, “Groups can be stupid, people gathering to make themselves feel better by making others feel worse. Keep doing what you do.”

Once we were finished she came over to look. She reached behind me and took a tuft of cream roving- “Do you see this? Everybody thinks they want to produce from this kind of soft, creamy fleece.” She brushed it against my cheek so that I could feel its softness. I glanced over at the pile of wool from my flock, instead of cream colored and soft it was, even without burdock, gray, black and crimped. “A sweater or hat made from this wool,” Val said holding up the little tuft, “won’t last more than a few years. But this wool,” she smiled and pointed at ours, “will make beautiful sweaters, hats, mittens that are beautiful AND durable, but most people don’t know that. I would take your wool over that any day.” I smiled as if she had complimented my child.

We gathered the carded wool, bagged it and wrote our name on the tag. We took the burdock-bunch home with us to leave in the woods so that the birds and small rodents could make winter nests with it. The next time we see our wool it will be transformed into beautiful yarn.

We said our goodbyes and drove around the circle, past the house sitting next to the mill. It struck me, this deception of appearances. If I didn’t know better, the mill could be a simple garage, not a place filled with magic, a place of transformation; from imperfect fleece to yarn, and from self-conscious experimenter to more confident shepherd.

Check out this cartoon by Robert Leighton in the New Yorker this week: